The story behind the speech: ‘The Man in The Arena,’ by Teddy Roosevelt

Published on February 15, 2025

On April 23, 1910, former President Theodore Roosevelt delivered one of his most famous speeches at the Sorbonne in Paris. The speech, titled “Citizenship in a Republic,” is perhaps best known for the passage referred to as “The Man in The Arena”:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

This powerful passage has resonated with millions over the years. Schoolchildren memorized it. Leaders remembered it. And it returned to the spotlight a few years ago by Brene Brown who took it as inspiration for her book Daring Greatly.

“The Man in The Arena” passage has been interpreted as a call to action, a reminder to pursue one’s goals fearlessly, and to live a life of resilience, despite the obstacles and failures that are sure to come along the way. Roosevelt’s words were not merely the result of his rhetoric or the occasion, however; they were deeply rooted in his own life experiences—tragedy, personal loss, illness, and fierce determination.

By examining these formative moments and the political context in which the speech was given, we can begin to understand the full impact of Roosevelt’s words and why they still speak to us today.

Early struggles: A childhood defined by illness

Theodore Roosevelt was born on October 27, 1858, to a wealthy family in New York City. The son of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. and Martha Bulloch, he was raised in a life of privilege.

Despite this, Roosevelt’s childhood was anything but easy.

Suffering from severe asthma, he spent much of his early years in poor health. His asthma attacks were so intense that they often left him feeling physically incapacitated, making him feel vulnerable and weak. From a very young age, Roosevelt was determined to overcome these obstacles. His father pushed him to persevere and build his strength, refusing to accept that his child might be too weak to survive to adulthood.

His father pushed him to persevere and build his strength, refusing to accept that his child might be too weak to survive to adulthood.

This attitude would shape the rest of Roosevelt’s life. His physical struggles with asthma left an indelible mark on him. Instead of succumbing to them, he chose to engage with life head-on. His decision to become a boxer, a wrestler, and a horseback rider—activities that he excelled in later in life—was a direct response to his physical challenges. Roosevelt wasn’t simply interested in maintaining his health; he wanted to prove to himself and others that he could overcome what seemed impossible.

Life-changing loss

Roosevelt’s personal challenges were not limited to his physical health. At the age of 19, he experienced the devastating loss of his father after a brief battle with cancer. The grief was overwhelming for Roosevelt, who was especially close to his father. He later reflected that his father had been a beacon of strength, and losing him left a void that was difficult to fill.

Inspired by his father’s legacy of strength and determination, Roosevelt pushed forward, channeling his grief into action. At the time of his father’s death, he was at Harvard University, and, although the weight of the loss was heavy, he poured himself into his academic work and extracurricular activities.

His father’s death was a turning point in his life. Instead of retreating into bitterness or despair, he embraced the idea that life must go on, and the best way to honor those who had passed was to live boldly and with purpose.

This mindset was what helped him cope with the second great tragedy of his young life. Just a few years later, when Roosevelt was 25 years old, his mother, Martha, succumbed to typhoid fever on the same day his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt died in childbirth.

On Valentine’s Day 1884, 25-year-old Roosevelt became a widow and the father of a daughter who he named after his deceased wife, Alice. His wife, whom he had married just a few years earlier, had shared his intellectual curiosity and adventurous spirit.

He later penned a heart-wrenching letter to his sister, in which he wrote, “The light has gone out of my life.” But once again, rather than succumbing to despair, Roosevelt retreated into a period of self-reflection, where he famously spent several years living in the Badlands of North Dakota. Here, Roosevelt worked on rebuilding himself, focusing on physical exertion and mental discipline.

“The light has gone out of my life.”

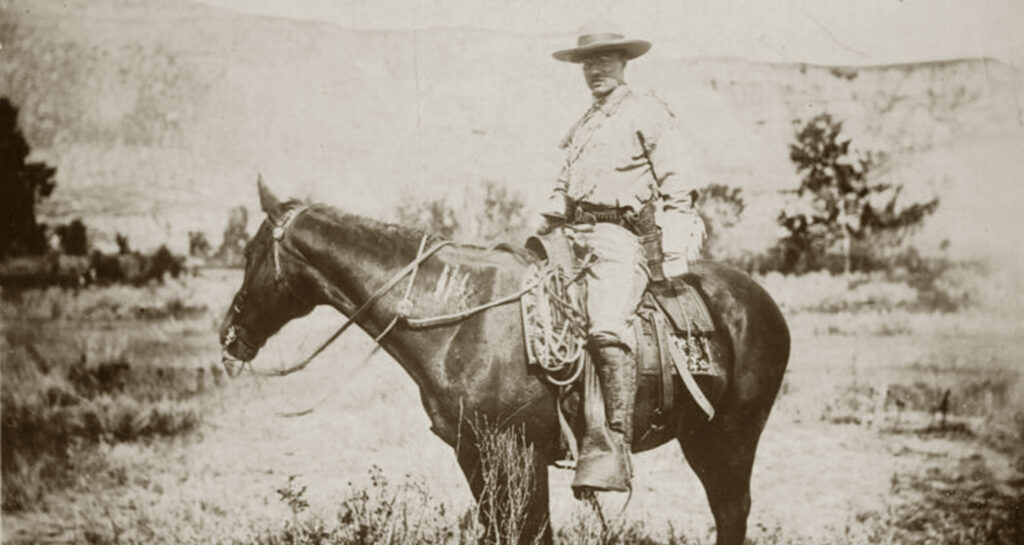

Roosevelt’s time in the Badlands was a pivotal point in his personal development. He confronted the depths of his grief and loss but also found the space to reevaluate his life, his goals, and his purpose. His time as a cowboy, riding horses, working with cattle, and building a business from scratch, reinvigorated him. This phase of his life not only restored his health, but also reinforced his belief in the value of hard work, discipline, and endurance.

It was during this time as a cowboy that Roosevelt developed the resilience that would serve him throughout his career. When he eventually returned to public life, he did so with renewed vigor, determined to make a difference in the world, and eventually, he married again and had five more children. His personal history of tragedy and hardship had shaped him into someone who valued action over inaction and bravery over retreat.

The struggles of his siblings: Family adversity

Not every member of the Roosevelt family coped with the grief as Teddy did. While he faced his own tragedies, his siblings added weight to his already heavy burden. His brother, Elliott Roosevelt, struggled with alcoholism throughout his life. His struggles with addiction and the toll it took on the family further solidified Theodore’s role as the family pillar and patriarch. In many ways, Theodore’s work ethic and his belief in responsibility were a reaction to the challenges posed by his brother’s behavior.

Elliot’s addiction eventually drove him to leave his wife and their daughter, Eleanor Roosevelt. Theodore’s sense of duty extended beyond his nuclear family, and he took on the role of a protector and became Eleanor’s father figure. Both within the Roosevelt extended family and in the broader political arena, Roosevelt rose through the ranks of leadership during this time.

Among the responsibilities required during this difficult time for the Roosevelts, Theodore often had to phone a doctor when a woman would come forward claiming they had a child with his brother Elliot. Instead of quickly dismissing them, Theodore’s sense of duty and responsibility led him to have the family doctor analyze the babies and determine if they could be his brother’s. Some were, and Theodore made payment arrangements when necessary, recognizing his own responsibility towards these children.

Political and historical context: “The Man in the Arena”

By the time Roosevelt delivered the words now known as the “Man in the Arena” speech in 1910, he was already a seasoned public figure. Having served as president from 1901 to 1909, his time in office had been marked by significant reforms, such as his trust-busting policies and his establishment of national parks, which made him a beloved figure in American politics.

By 1910, however, Roosevelt’s political landscape had changed. He was grappling with the growing divide in the Republican Party, particularly between the progressive faction he had championed and the conservative wing.

The speech he delivered at the Sorbonne was a direct response to these challenges. Roosevelt was advocating for active citizenship, personal responsibility, and the belief that individuals should strive to contribute to the greater good, no matter the odds or the criticisms they might face.

In many ways, the speech encapsulated Roosevelt’s own life philosophy. He had never been one to shy away from criticism or adversity, and he had never been content with merely existing. Roosevelt had faced his fair share of detractors—whether it was the media, political rivals, or even his own family—and yet, through it all, he remained resolute in his belief that the value of life comes not from the opinions of others, but from the pursuit of noble and worthwhile goals. This sentiment was at the heart of his “Man in the Arena” passage, where he implored the audience to live life with purpose, even in the face of failure and hardship.

The political context of Roosevelt’s speech was one of increasing tension within the American political landscape, and his words resonated as a call for unity and courage. He called on Americans to not only embrace the struggles but also to take pride in their fight against them.

As he looked back on his own life, filled with loss, struggle, and hardship, Roosevelt’s commitment to personal resilience and national progress was clearer than ever.

Conclusion: Roosevelt’s enduring legacy

Theodore Roosevelt’s famous speech at the Sorbonne, and especially the “Man in the Arena” portion, stands as a testament to the strength of character he developed through his own adversities.

His early life struggles with health issues, the loss of his parents, the death of his first wife, and his difficult family dynamics all contributed to the resilient, action-oriented philosophy he championed throughout his life. Through these trials, Roosevelt became the “man in the arena”—a leader who understood that true success comes not from avoiding failure, but from embracing life’s challenges with courage and determination.

Roosevelt’s story reminds us that life is never free from obstacles. It is how we respond to these challenges that define us. Whether we are overcoming personal tragedy, battling with illness, or facing criticism in the public eye, the lesson remains the same: it is not the critics who matter, but the ones who dare to act, who dare to struggle and fail, and who dare to continue the fight for what they believe is right.

I love it!

I love Teddy Roosevelt! He has the right attitude about life.

There’s a President to inspire us for sure. I think we have more than one “Man in the Arena” right now.

LOVE this.