The fascinating history of coffee culture in America

Published on November 1, 2025

America may run on Dunkin’ today, but once upon a time, it was a tea-drinking nation. In fact, for much of our early colonial history, coffee was considered exotic. It was simply too bitter, too foreign, too “continental.” But fast forward to today, and the United States is the largest consumer of coffee in the world, with more than 150 million Americans drinking it daily. How did we get here?

The story of coffee in America is as much about rebellion, immigration, and faith as it is about taste. From Boston patriots dumping tea into the harbor and choosing coffee as their protest beverage to the Roosevelts sipping cappuccinos in New York cafés inspired by Europe, to Italian Catholic immigrants introducing espresso bars to our cities, coffee has woven itself into the American identity in unexpected ways. This is not just a story about caffeine; it’s about culture, politics, and belonging.

The Boston Tea Party and coffee as an act of rebellion

To understand how America became a coffee nation, we must begin with tea. In the early 18th century, tea was the drink of the colonies. It was elegant, ritualized, and imported by the British East India Company. Coffee, by contrast, was still considered an outsider beverage, popular in European coffeehouses but not yet mainstream in the colonies.

That all changed in 1773. When the British imposed the Tea Act, colonists balked at the taxation. The infamous Boston Tea Party was not simply a rejection of British control, it was a cultural reset. Bostonians threw chests of tea into the harbor, symbolically declaring: We will not be ruled by Britain, nor will we be defined by their beverage of choice.

Almost overnight, coffee became the patriotic alternative. To sip tea was to declare loyalty to Britain; to drink coffee was to stake your claim as an American rebel. Coffee was more than caffeine, it suddenly became a revolution in a cup. Abigail Adams even wrote to her husband that she and her friends had given up tea entirely, choosing coffee to demonstrate their solidarity with independence.

That symbolic shift planted the seed for America’s enduring relationship with coffee. While tea never fully disappeared, its dominance was permanently undermined. Coffee became the drink of choice not because it was easier or tastier, but because it was American.

The Roosevelts and the birth of the coffeehouse in New York

If Boston gave coffee its political symbolism, New York gave it its cultural home. In the 19th century, Americans were traveling more widely, and European influence began reshaping city life. Coffeehouses were long a fixture in London, Paris, and Vienna but were still rare in the United States. That is, until the Roosevelts entered the scene.

The Roosevelt family (yes, that Roosevelt family) had a deep fondness for coffee. Teddy Roosevelt was famous for drinking a gallon of coffee a day. His son later quipped that his father’s coffee was “more in the nature of a mug of warm coffee-flavored water than anything else.” But beyond sheer consumption, the Roosevelts helped make coffee culture fashionable.

Inspired by their travels in South America, where they saw firsthand how central coffee was to daily life, and in Europe, where café society flourished, the Roosevelts were instrumental in opening one of the first coffeehouses in New York City. It wasn’t quite the bohemian artist haunt of later decades, but it was one of the first attempts to bring the café concept across the Atlantic.

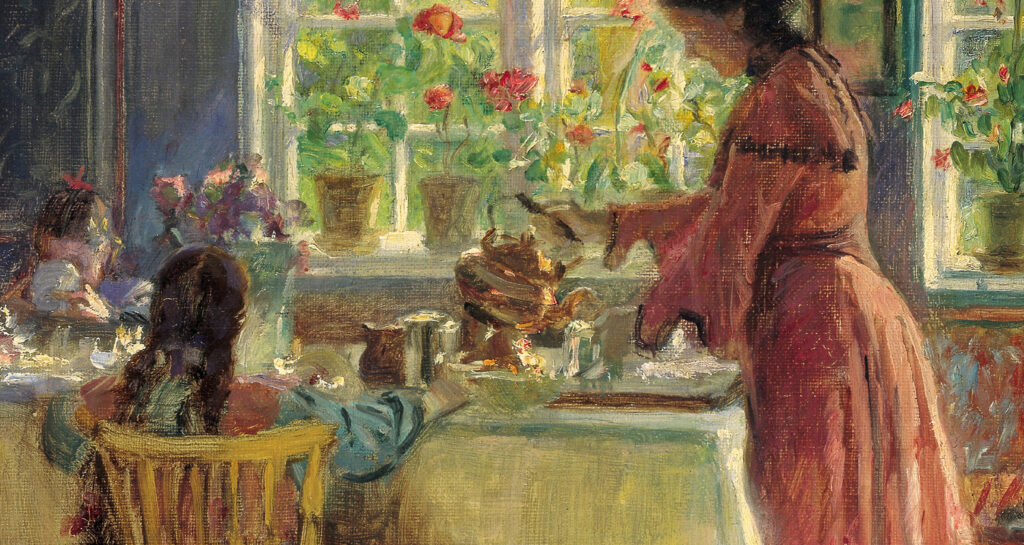

This coffeehouse helped set a precedent: Coffee was not just a drink to be gulped in the morning, but an experience. A place of conversation, politics, creativity, and community. It laid the groundwork for the coffee shop culture that would explode in the 20th century, from Beatnik espresso bars in Greenwich Village to Starbucks in Seattle.

Italian Catholics, espresso, and the rise of immigrant coffee culture

Perhaps the most overlooked chapter in America’s coffee story belongs to Catholic immigrants, particularly Italians. When waves of Italian immigrants arrived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they brought with them not just their language and cuisine, but their rituals. And one of those rituals was coffee.

In Italy, espresso is not just a drink, it’s a daily sacrament. Quick, strong, and communal, it’s often consumed standing up at the counter. Italians in America recreated this culture in the neighborhoods where they settled, opening small cafés and espresso bars that quickly became community hubs.

These establishments weren’t glamorous. They were often humble, family-run spaces, serving espresso in thick ceramic cups, alongside biscotti or cannoli. But they introduced Americans to a new way of drinking coffee, one that remains fast, intense, and social.

For Catholic immigrants, the café was also a cultural anchor. Coffee bars doubled as spaces of belonging, where faith and family intertwined. Many cafés sat in the shadow of Catholic churches, and Sundays often involved both Mass and espresso. In a subtle way, Catholicism gave coffee its sacramental quality in America; not literally as a ritual of faith but as a practice tied to family, community, and the rhythms of daily life.

By the mid-20th century, espresso culture had spread beyond immigrant neighborhoods. Beat poets, jazz musicians, and young intellectuals adopted espresso bars as their creative haunts. The humble Italian café had blossomed into a symbol of counterculture cool.

Coffee as a national identity

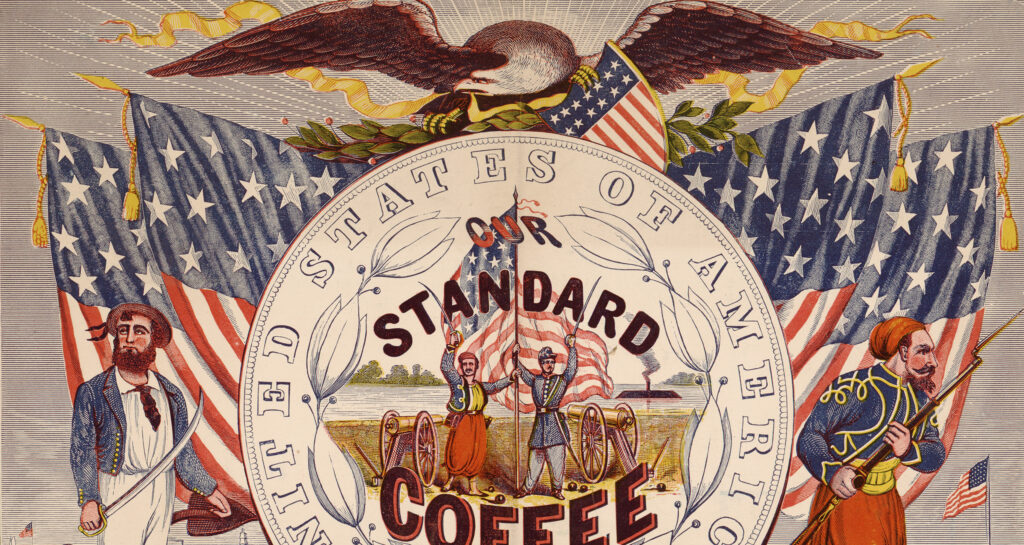

By the time the 20th century reached its midpoint, coffee had not only overtaken tea, it had become the American drink. Soldiers in both World Wars were issued coffee rations, and “a cup of joe” became synonymous with patriotism and grit. In the 1950s, the percolator was a staple of every suburban kitchen, brewing endless pots for the nuclear family.

And then, in the late 20th century, coffee became aspirational again. Starbucks, founded in Seattle in 1971, transformed coffee from a kitchen necessity to a lifestyle statement. The latte, cappuccino, and macchiato that were once confined to immigrant neighborhoods, were suddenly mainstream. Coffeehouses returned to their European roots: a place to gather, talk, and linger.

Today, America leads the world in coffee consumption — not necessarily in quality (though specialty coffee roasters are changing that) — but in sheer volume. We drink it everywhere: in drive-thru windows, office break rooms, hipster cafés, and on the sidelines of soccer practice. Coffee is no longer rebellion; it’s routine. But the roots of that routine are far from ordinary.

Why coffee matters to the American soul

If you trace the story back to the Boston rebels rejecting tea, the Roosevelts importing café society, and Italian Catholics infusing espresso into immigrant neighborhoods, you see a pattern. Coffee in America has always been more than a drink. It has been a marker of identity.

- Political identity: In the Revolution, to drink coffee was to reject Britain and claim American independence.

- Cultural identity: In New York, coffeehouses became the meeting grounds for politics, art, and civic life.

- Immigrant identity: For Italians and Catholics, espresso bars offered cultural continuity and belonging in a new land.

- National identity: For soldiers, workers, and families, coffee became the fuel of democracy itself.

It’s no wonder that today, “grabbing a coffee” is shorthand for connection, whether a first date, a business meeting, or catching up with a friend. Coffee is America’s most democratic beverage; it’s welcoming, versatile, and always evolving.

Coffee, more than caffeine

From the Boston Harbor to the Bronx espresso bar, from Teddy Roosevelt’s mug to Starbucks’ green siren, the story of coffee in America is layered, fascinating, and profoundly human. We may not think about it as we sip our lattes in the morning rush, but each cup carries echoes of rebellion, family, faith, and reinvention.

Coffee is no longer a symbol of defiance against Britain, or the exclusive ritual of Italian immigrants, now it belongs to all of us. And yet, it retains that special quality of being more than what it seems. Coffee is warmth. Coffee is community. Coffee is culture in a cup.

So the next time you sip your daily brew, remember: You’re not just drinking caffeine. You’re part of a centuries-old story about identity, belonging, and the way ordinary rituals shape who we are as a nation.

The shortcoming of this article is its latent praise for Starbucks and its woke, manipulative trappings.

So, what does it say about me as an American that I have always hated coffee (tastes disgusting in my opinion) and find the idea of needing a daily stimulant to function completely abhorrent?

I love coffee! Especially stong Mexican coffee with Mexican sugar & a little evaporated milk 😃😋