I have a genetic condition: Should I edit my future children’s DNA?

Published on April 14, 2025

It was a regular Friday morning in snowy February when I suddenly started feeling dizzy, and I could feel my heart palpitating in my legs. I got up from my desk and walked next door to ask for help. I work with nurses, so they manually took my pulse and determined that my heart was racing—somewhere between 130 and 150 beats per minute. Way too high for someone just sitting at a desk. Within minutes, I was under observation in an emergency room.

A diagnosis I didn’t see coming

But really, it had all started a few weeks earlier. I’d been feeling unexplained fatigue and had one random fainting episode, which I recovered from quickly. When I called my parents to let them know what was going on, my dad immediately urged me to get tested for ARVD-C—Arrhythmic Right Ventricular Dysplasia Cardiac. It’s a rare genetic condition in which a small deviation in the right ventricle of the heart makes it prone to arrhythmias, potentially leading to heart attacks and strokes. Just as we can inherit dimples, eye color, or hair texture from our parents, we can also inherit a flawed heart.

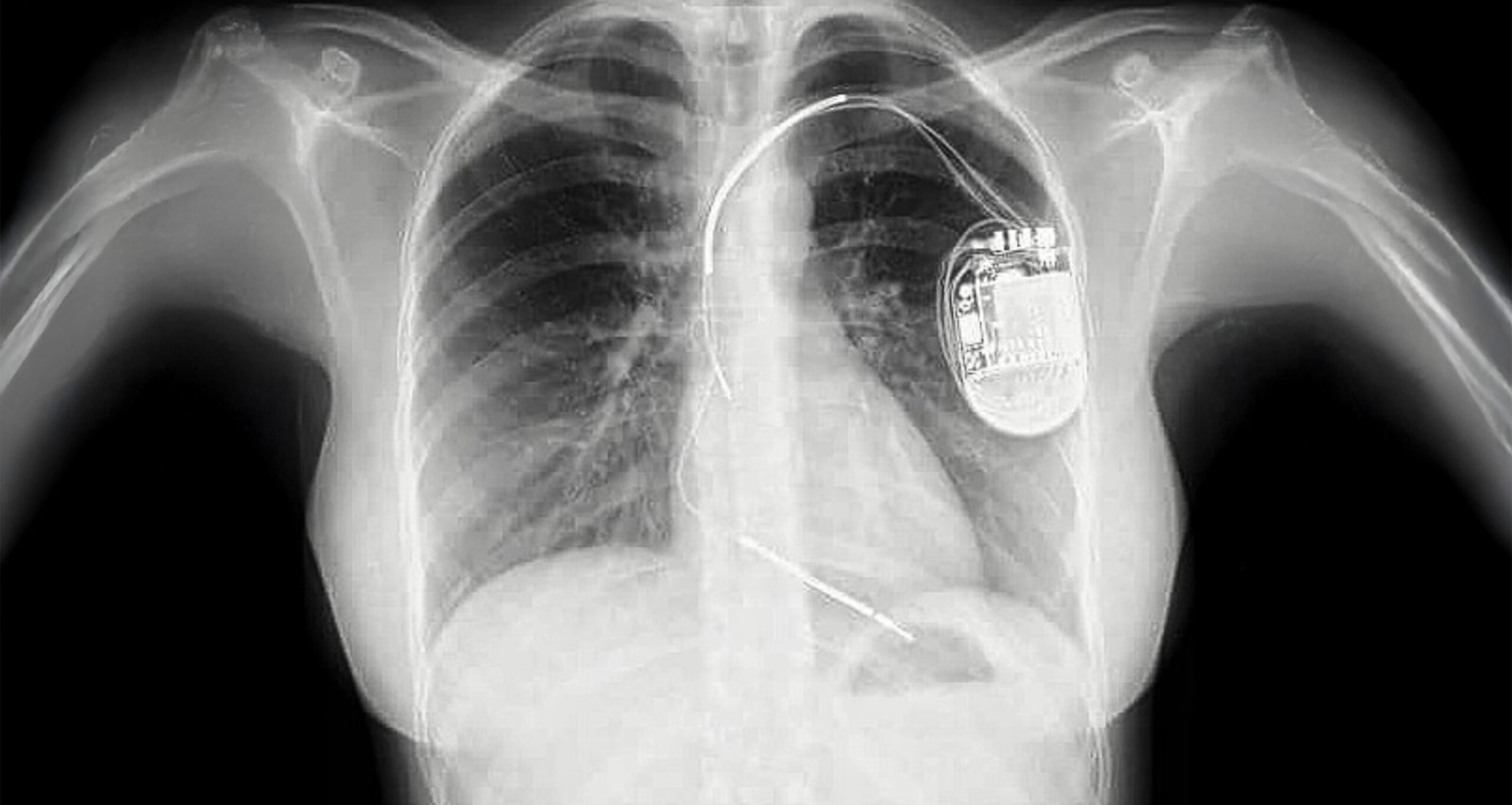

I spent four days in the hospital, with all kinds of cardiologists coming in and out. Eventually, I left with a formal ARVD-C diagnosis. The next step? Surgery to implant a cardiac defibrillator in my chest. There’s no cure for ARVD-C. The dysplasia can’t be operated on, and no pill can change the structure of the heart. My doctor explained that survival depends on how fast you can get to an ER and be revived. A healthy lifestyle might buy you time – but it won’t save your life.

Survival depends on how fast you can get to an ER.

I was one of the lucky ones. Most people with ARVD-C never know they have it. When undiagnosed, it’s often labeled as sudden death because the first symptom is often the fatal event. Like my uncle – 23 years old, fit, felt dizzy, and decided to take a nap. He never woke up. The doctors said it was a stroke in his sleep. Now, we assume it was due to ARVD-C.

A few weeks after my diagnosis, I lay on a surgical table while a biomedical engineer implanted the defibrillator—a small device ready to shock my heart back to rhythm if I ever go into arrhythmia. I wasn’t scared, honestly. I had seen my dad go through it, and there’s something reassuring about watching your parents face a challenge calmly – it makes you calm, too.

Once I had the defibrillator and the stitches healed, my doctor encouraged me to live life as usual. I took that to heart (pun intended). I trained for the Chicago Sandblast, a two-day ultimate frisbee tournament on the beaches of Lake Michigan. Later, I hiked Mount Rainier in the snow. Not long after that, I took close friends to my Caribbean hometown, where we scuba-dived through reefs and shipwrecks. I didn’t take any of that—or my ability to do it—for granted.

Hope was all around.

The promise and complexity of gene editing

My cardiologist also told me that incredible new research might soon eliminate this condition – and many others – entirely. Since ARVD-C is genetic, a simple gene edit could remove it from the DNA strand and eliminate the risk for future generations. While I don’t hate my defibrillator, the idea of my children not needing one – unlike my father, a few cousins, and me – is incredibly appealing.

When my dad was diagnosed, a doctor advised him not to have children who could inherit ARVD-C. My dad chuckled – until he realized the doctor was serious. He never regretted having his four children. Knowing I’d inherit his condition didn’t change how much he wanted us or how grateful he was for our lives. But that doctor’s advice stuck with me. How many people, hearing the same advice, chose not to have children? It’s heartbreaking to think about the lives never lived and the silent suffering of those who believed their existence would be a burden.

Doctors have different philosophies, and it shows in their guidance. So when mine brought up gene editing, I was intrigued. He made it sound simple – but it’s anything but. It’s riddled with ethical and philosophical questions, the same ones that inspired Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein – which, let’s not forget, is a horror story. Still, gene editing is one of the most promising fields today. It offers hope, not just for managing disease, but also for eradicating it.

What’s currently available

As of April 2025, most gene editing happens through CRISPR or embryo manipulation (euphemistically called “selection” or “therapy”).

CRISPR-Cas9 is the most advanced and widely used tool. Since 2012, when Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier published their groundbreaking research, it has changed medicine. By using a guide RNA to target a specific DNA sequence, the Cas9 enzyme acts like molecular scissors, cutting DNA at the targeted site. The cell then repairs the break, allowing for gene correction, insertion, or deletion.

For their work, Doudna and Charpentier were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry:

“This technology has had a revolutionary impact on the life sciences, is contributing to new cancer therapies and may make the dream of curing inherited diseases come true.” — Chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry

Still, as precise as CRISPR is, it carries risks—like any medical procedure. It’s one thing to mess up stitches or have a bone heal wrong. A gene-editing mistake? We just don’t know what that could mean yet.

I joked with my family about it. I told them about my conversation with the cardiologist, and we all agreed—laughing—that we couldn’t risk accidentally deleting the genes responsible for good looks and excellent humor.

Right now, CRISPR doesn’t change the DNA passed down to children. It can edit specific cells in the body, but those changes aren’t heritable. There’s hope that someday we’ll use it to eliminate genetic diseases from the family line—but not yet.

And then comes the ethical can of worms: what should we edit? Should we design our children? Part of the beauty of our DNA is that it’s the mysterious, sacred blend of generations of love.

The ethical dilemma of embryo manipulation

Embryo selection and therapy is, unfortunately, the most commonly used technique today. But it doesn’t prevent a genetic condition – it avoids it by selecting embryos that don’t carry it. That means using IVF, testing the embryos, and discarding the ones with the condition.

If this option had been available to my parents, I wouldn’t have been cured. I simply wouldn’t have been born. Or more precisely, I would have briefly existed, but never lived.

Or more precisely, I would have briefly existed, but never lived.

That thought breaks my heart. Parents making that choice often do so with love and guidance from doctors. But my life has been worth every second. ARVD-C doesn’t change that.

Embryo therapy—editing an embryo’s genes before implantation—is slightly more accepted, but still raises issues.

First, IVF rarely works with just one embryo. Doctors usually implant several, knowing not all will survive. So practically, embryos are more likely to die from IVF complications than from the condition we’re trying to “fix.”

Second, it alters the sacred act of conception. Creating a child should reflect unity and love. Gene editing risks turning life into something we customize rather than something we welcome. It shifts our mindset—from gratitude to control, from gift to product.

What the future might hold

Researchers are now refining gene-editing tools for germline editing—heritable changes passed down through generations. One promising development is prime editing, a technique that allows for even more accurate edits with fewer unintended mutations. Base editing is also advancing, offering single-letter DNA changes without cutting the DNA strand, reducing potential side effects.

These methods could one day correct genetic disorders like ARVD-C without destroying embryos or compromising the dignity of life.

Another area of study is mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT). While it targets mitochondrial DNA, it opens the door to similar methods for nuclear DNA. If such treatments can be safely done before conception – without selecting or discarding embryos – they might be a morally acceptable option. But the motivation must always be healing, not enhancing.

A life worth living

At first, being diagnosed with a genetic condition felt like a death sentence. But now – with a diagnosis and a defibrillator – I’m more likely to die from many other things. Honestly, my clumsiness, questionable driving, and thirst for adventure are bigger threats.

When I was first diagnosed, I remembered C.S. Lewis’s 1948 essay On Living in an Atomic Age, where he writes that we shouldn’t obsess over death by atomic bomb. Instead, we should make sure death finds us living. That’s what I’m focused on.

It’s been two years since I got my defibrillator. I haven’t been shocked once. My dad? He’s been shocked six times. I asked him what it feels like, and he said it’s like being hit by thunder or getting punched really hard in the chest. I don’t have a frame of reference for either – but if and when it happens, it’ll find me unprepared… and fully alive.

In the end, life isn’t about having flawless DNA. Even perfect genes don’t guarantee a painless existence. As they say, life is a card game – not about the hand you’re dealt, but how you play it. A handful of aces may make the game easier, but it doesn’t make you a better player.

So, will I edit my genes so my children can have a different hand? No. Not for now. Not until there’s a way to do it without ending anyone’s life. In the meantime, I’ll keep playing—and make sure my kids know how to play, too.

After all, I’m proud to say I’m enjoying the game – and I’m winning. And ultimately, that’s what life is all about.

Thank you for this thoughtful article – it is one thing to say we are “pro-life” – it is another thing to wrestle with very personal challenges and still make faith-informed choices.

We as well have cystic fibrosis in our family, one of our kids has it and the other three don’t. We’ve been through the wringer with doctors’ good and bad advice, the worst was when I was pregnant with my 4th and the cold doctor said for 7 months “you can terminate your pregnancy” and that was at a Catholic hospital!

The best advice was a doctor that told me that a cystic fibrosis baby she delivered was the best gift their family ever received.

Our little girl is too! She’s a joy and a gift. I wouldn’t want to “fix” her, you’re right it’s the life in the years not the years of life!

Such a well researched and thoughtfully concluded article. Thank you!